Whether you’re a seasoned infrared pro or not, you’ve likely heard about our IR Chrome filter or at least seen its stunning effects. However, if you’re unfamiliar, the IR Chrome filter is our digital emulation of the long-gone iconic Aerochrome false color infrared film. If you’ve ever wondered how this filter came to be and why no one else makes it, read on for an in-depth history of the filter that put Kolari on the map.

A Brief History of Infrared Photography

Infrared light was first discovered in 1800 by Sir Frederick William Herschel while conducting an experiment to measure the temperatures of the different colors of the light spectrum. Robert Williams Wood took the first infrared photograph in 1910 on experimental film plates. During WWI, the military used IR-sensitive plates for aerial photography. Infrared photography became a valuable tool for cutting through atmospheric haze and identifying enemy targets from airplanes. By the 1930s, black and white IR film was commercially available and became widely popular with photographers, scientists, and even Hollywood. To learn more about the full history of infrared photography, check out our article here.

WWII – The Development of Aerochrome for Military Use

When WWII began, militaries deployed the use of infrared aerial photography as they did in WWI. The unique ability of IR to differentiate false greenery used for camouflage from real, live foliage (known as the “Wood Effect”) was a powerful asset, and many used it in hopes of gaining every advantage possible on the battlefield. However, a new paint that could mimic the Wood Effect was developed to render this photographic method useless.

A new tactic needed to be born to get back the upper hand. Kodak and the US Military worked together to create a false color infrared film — Aerochrome III Infrared 1443. With this new color IR film, the chlorophyll in plants would photograph as hot pink instead of a snowy white, making camouflage detection possible again without the Wood Effect paint getting in the way.

The 1960s Psychedelic Movement

The psychedelic movement of the 1960s was a very surreal and colorful time. Unique and unusual colors were popping up everywhere, especially in the artistic world. One of the spearheads of this movement in the photography sector was Karl Ferris, a British fashion photographer turned legendary music photographer. Karl had been using filters and innovative techniques to create funky images with psychedelic colors. When he sent them through the Kodak London lab, the manager was very intrigued. He had never seen anything like this before.

Aerochrome had just been released from the military, and Kodak wanted to push it into the commercial market but didn’t know how to make it suitable for commercial audiences. The lab manager asked Karl if he could find some sort of technique to make the film usable. Coincidentally, Karl had previously used Aerochrome for photographing foliage and heat blasts on the battlefield during his time as an aerial photographer in the Royal Air Force, so he was familiar with what it could do. Kodak gave him cases of the film to test and experiment with.

It took a while to get the right combination of lighting, filters, and processing to create good results, but Karl eventually figured it out. Black and white infrared film had a tendency to make people look ghoulish, but with the Aerochrome, Karl was able to get passable skin tones while the rest of the colors “freaked out,” as he likes to say. His experiments resulted in the distinctive colors we know and love with today’s IR Chrome filter — the hot pink or crimson red trees and bright blue skies.

This look blew up in the ‘60s psychedelic scene, and both Karl’s work and the Aerochrome film became very popular. Karl’s most prominent work has been his music photography during this time. He shot for artists such as Cream, Donovan, The Hollies, and Jimi Hendrix. His most iconic pieces were the album covers he shot for Jimi Hendrix and Donovan using Aerochrome.

2007 – Kodak Discontinues Aerochrome

With the introduction of digital cameras in the late 1990s, the demand for film dropped significantly, even more so for infrared film. In 2007, Kodak decided to discontinue many of its IR film stocks, including Aerochrome, due to the decrease in sales. Today’s revival of analog photography has inspired many film manufacturers to bring back some of their discontinued film stocks, but sadly, Aerochrome is gone for good.

Karl was an early innovator of color infrared photography. It was the height of his career, so when Kodak discontinued Aerochrome film and the remaining stock ran out, he wasn’t able to shoot much anymore. With the advent of digital photography and full spectrum conversions, Karl dove right in, but he wasn’t happy with the results. The colors were never quite right. The images needed a lot of post-processing in Photoshop, but it was impossible to replicate the results he had gotten with the Aerochrome film.

He wasn’t the only one trying to bring this iconic look back to life through digital processing. Many other photographers tried their hand at recreating it, and some came close. Using a Yellow #12 filter, the same used in color IR film photography, was a common technique, but the post-processing was an ordeal and often didn’t produce clean results. Our 550nm filter was another commonly used technique with a similar outcome. Eventually, however, the determination of one photographer would succeed in this quest in a way the others couldn’t.

2019 – IR Chrome is Born

Yann Philippe, a French photographer, has always been interested in alternative photographic techniques, such as cyanotypes and Kirlian photography. He enjoys creating imaginary fantasy worlds in his work. So when he discovered infrared in 2008, he knew right away that he had to give it a try. He joined the emulation quest, exploring methods yet to be tried. While others attempted to recreate the look using post-processing, Yann’s goal was to achieve the colors in camera without the need for complicated processing techniques.

Between 2010 and 2014, Yann had all but abandoned infrared photography. He discovered that IR conversions had become more mainstream in 2014, got himself a full spectrum camera, and threw himself back into his emulation research, picking back up right where he left off in 2008. He experimented extensively with colored gels, then progressed to glass/acrylic filters to test different layer combinations and calculate their transmission curves.

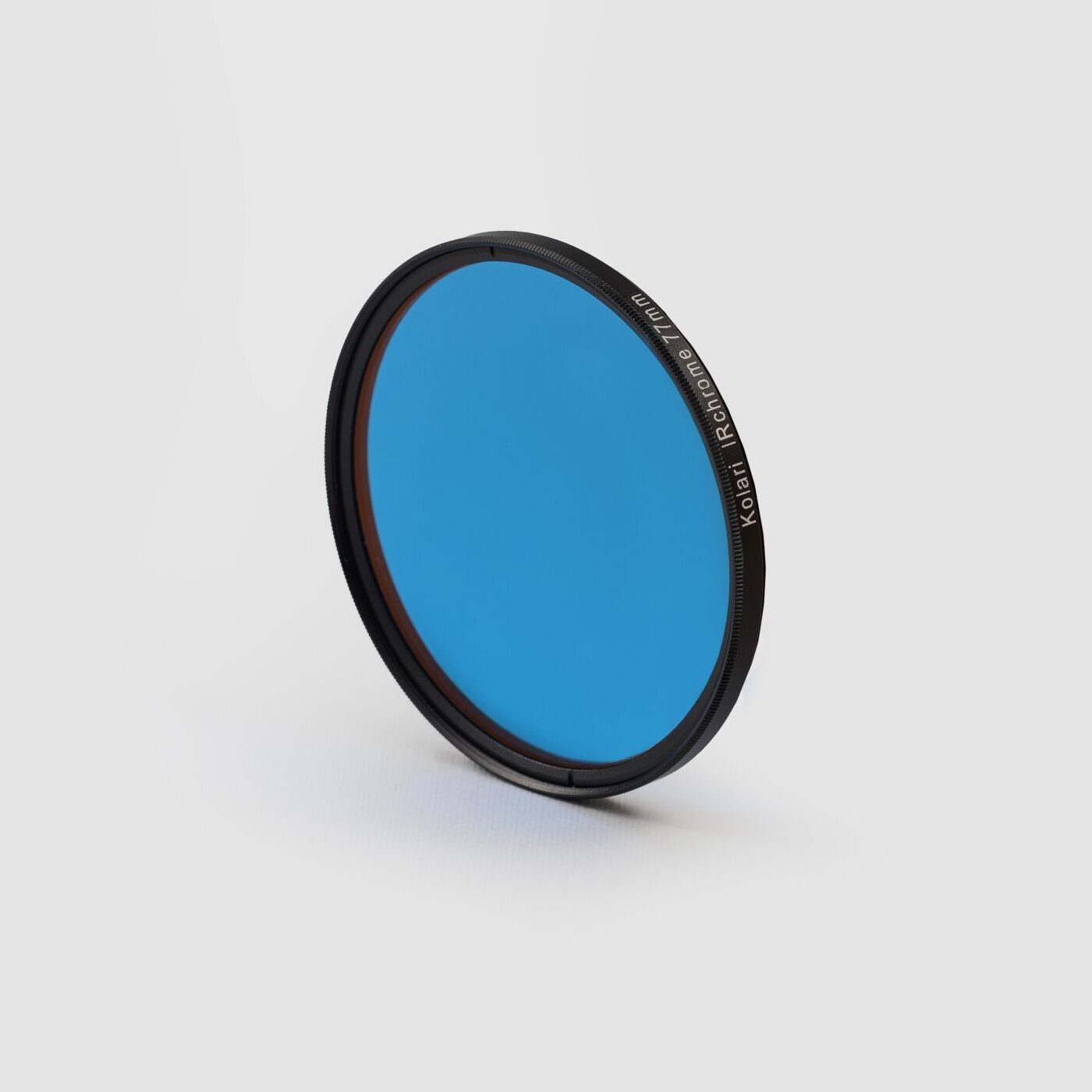

After years of trial and error, he finally produced the right transmission curve to create the results he was after. He then partnered with Kolari to create a new lens filter to recreate Aerochrome film for the digital infrared generation. In early 2019, our best-selling IR Chrome filter was born. Yann performed many tests comparing the IR Chrome to the original Aerochrome film. The results were very similar. Even Karl Ferris reached out to us to test an early prototype of the filter and agreed that the resulting colors were very close to his original photos from the ‘60s.

Though this filter is only a few years old, its history is a fascinating one that spans decades of technological innovation and creative experimentation. From the development of Aerochrome during WWII to Karl Ferris’s iconic album covers in the 1960s to Yann Philippe’s digital emulation of the film in the 21st century, the story of IR Chrome is a testament to the enduring power of creativity and innovation in the world of photography. Today, photographers continue to use IR Chrome to capture stunning images with the same surreal and colorful effects as the original Aerochrome film. And we can’t wait to see where the creatively innovative spirit of this incredible community will lead next.

2 Responses

I too played with Aerochrome in the 60’s and was sorry to see it go. When I tried digital IR, I started with the 560 nm conversion, because I wanted color. I could play with channel swapping but it was never what I remembered. IR Chrome is what I remember. Regrettably, I have no idea what happened to those Aerochrome slides I shot 50+ years ago. Thank you Kolari.

Thanks for the interesting historical tour. Great article.