Photography Artist Feature: Sennen Powell

I’ve been doing photography for almost a decade now. I honestly don’t know how my passion started. All I remember was wanting a camera when I was ten, and I became addicted to the euphoria of a well-composed, correctly exposed, meaningful image. It was like brain ambrosia; I couldn’t stop. I admit I was initially terrible but luckily also very obsessive, and many thousands of photographs later, I have now placed in several competitions.

I started in wildlife photography, with Chris Packham as one of my inspirations. His work wasn’t as documentarian as most wildlife photography but tingling with fine art mystery and narrative. However, after I got my first phone, I realised the often high-contrast nature of their cameras made for amazing black and white photography. After that, I chased light everywhere, not just the kind bouncing off birds and flowers but anything, and I started to see the world in terms of contrast, intensity, and composition. Taking pictures became like making a sensory dictionary. The light was now my main subject; what appeared in my images was all manner of things, ranging from a fork to my hand to leaves.

For me, photography has become like breathing. I often process my environment by composing pictures in my head as I walk around. Seeing how things line up, angles and shades coalescing then separating as I pass by. It’s a need and an untangleable part of my life. Paying more attention to light and the sun, both of which have been at the centre of human spirituality for millennia, has slowed my mind and made me think more thoughtfully about the passage of time and changing mood of my environment.

I first discovered infrared photography through Richard Mosse’s work, and I immediately found the palate of blood pink and chemically poisoned blue to be intoxicating. And it was how it made reality seem so disturbing that caught my attention. I’ve always loved to estrange and twist the environment in my head so that objects become their own sitters. I would take pictures of lampposts like a human portrait—as if it had its own essence.

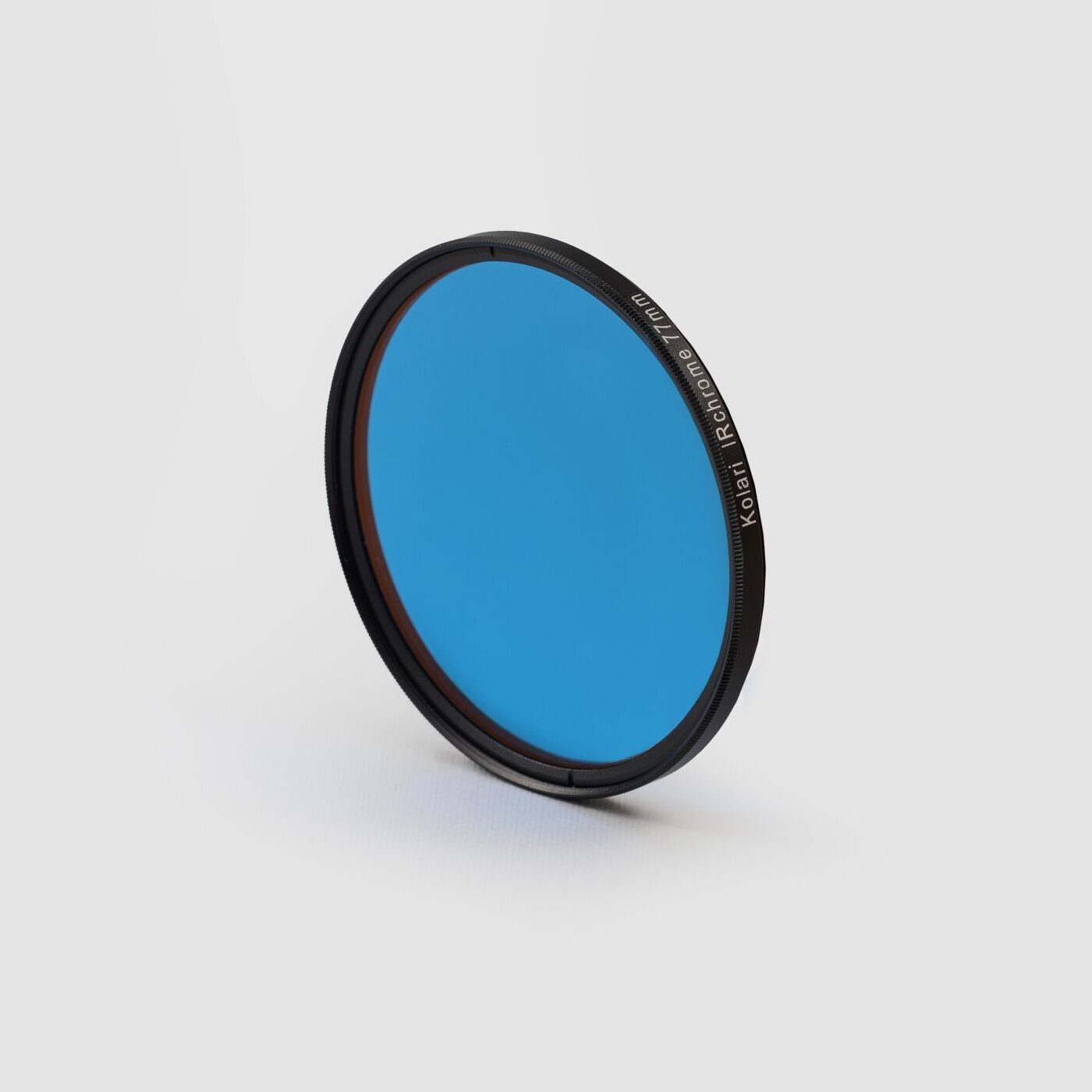

Infrared distilled what I had been chasing—a landscape of other. After dappling in black and white IR in the Scottish Highlands and finding it unsatisfying, I bought a secondhand Nikon D90 converted to 590nm. Being an amateur (and an impatient shopper), I didn’t know the significance of the different filter wavelengths. Instead of pictures coming out red and blue, they came out in a range of false colours, often pastel and sickly. The closest I got to the old Kodak Aerochrome film look was a pink milk colour. I found the pictures I took really synthetic and couldn’t find a place in my mind to like that aesthetic; I couldn’t see how I could use it to create meaning.

That was until I took my picture of the traffic lights. It was at a junction in the middle of Devon surrounded by an industrial park, and I had been obsessively taking pictures out of the car window for the last ten minutes. By some miracle, we stopped at the lights in just the right position. There were so many traffic lights, uselessly hanging around this soulless junction. The purpose of a traffic light is to guide you where and when to go, which made this mutated gathering of several of them ironic.

The object (traffic light) and its purpose (to guide) questioned its reality, and even more so than that, it was as if the unreality of infrared artificial objects seemed the most organic because everything else wasn’t real. It helped me fully understand what I wanted to convey with infrared.

I wanted to make surrealist photography. I wanted, like Dali (I was particularly inspired by his paintings), to take objects and imbue them with their own presence in an otherwise meaningless landscape. With nature a synthetic pink, I found that, for me, infrared took the artificial and gave it its own ecosystem, constructed by the subconscious of the human society—a landscape of our own collective imagining.

And even after my initial annoyance with it, I did return to black and white infrared. I found a place for it in my surrealist reality. Infrared often makes shadows seem more intense. Salvador Dali would often paint a world where the shadows have their own space with their own meaning, almost with a mind of their own, entirely unconnected from what was creating them. It also made me fall in love with clouds, which seemed smoother and less solid in infrared than visible light; it helped me bring out their personality, whether their grandeur or heavy background presence.

That is all extremely pretentious, but everyone has their own relationship with an image. For me, the quest for surrealism is what drives me. I continue to evolve how I take infrared images, and I hope that my time at the University of the Arts London will open up more avenues of creative thinking.

Sennen is a winner of our annual “Life in Another Light” Photo Contest.